As the world struggles to lay the foundations a new global climate deal in yet another round of annual UN-led negotiations in Lima, experts stress that it is the role of civil society organizations that is crucial to bring a change at the grassroots

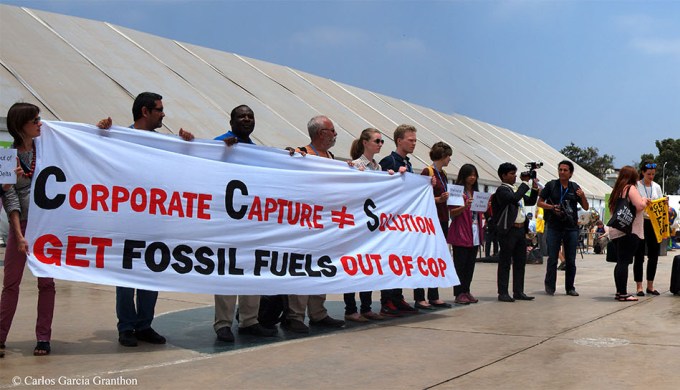

Civil society needs to augment its fight against climate change, say experts (Image by Carlos Gracia Granthon)

As multiple stakeholders gear up to hammer out a global agreement to combat climate change at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) summit in Lima, the glacial pace of negotiations on the subject, and the elusiveness of a workable solution among fractious nations has underscored the need for civil society organizations (CSO) to step up their engagement.

In India, a country of 1.25 billion people, where the impact of climate change is becoming increasingly manifest – be it in flood-ravaged Kashmir or Uttarakhand, or cyclone-whipped Visakhapatnam – the need for a multi-tier, multi-stakeholder approach to tackle climate change has never been greater.

Indian civil society engagement with climate change began much before the international community agreed on the UNFCCC. Indian NGOs like the Centre for Science and Environment have played a pivotal role in shaping the contours of government policy as well as the UNFCCC. Many others have played a vital role in pushing forth new laws, policies and strategies on climate change, hold governments accountable to their commitments as well as ensure that the poor and the vulnerable remain central to national climate change policy narratives.

The year 2015, say climate change experts, is especially propitious for emphasizing civil society participation and the way citizens talk about climate change. “The recent Ban ki Moon summit and post-2015 development debates underway offers a window of opportunity to build on the momentum of both conversations to articulate a climate change perspective rooted in people’s needs,” says Ankur Garg, Team Leader, Resilience and Climate Change, BBC Media Action (India).

The objective of putting people and their interests at the heart of climate change response, adds Garg, is the core of Climate Asia, a survey undertaken by BBC Media Action. Undertaken in seven Asian countries, till now it is the world’s largest survey of peoples’ daily experience of climate change. The idea behind the project, he adds, was to steer the climate change discourse away from the preserve of a policy space preoccupied primarily with science and politics, towards one that encourages peoples’ experiences to be at the heart of policy responses to climate change.

“It’s not about how climate change is communicated among diplomats and scientists but how one might talk about these issues with a taxi driver in Delhi, a housewife in Mumbai, or a smallholder in Bundelkhand,” explains Garg.

A 2012 report, Southern Voices on Climate Policy Choices: Civil society Advocacy on Climate Change, by a coalition of over 20 NGOs working in developing countries demonstrates that civil society is critical to policy processes that aim to tackle climate change and protect the poorest and most underprivileged communities from its impacts.

In her essay, Civil Society and the Integration of Climate Change Risks into Planning and Policymaking, Nella Canales Trujillo, Climate Change and Advocacy Advisor at Britain’s Overseas Development Institute, describes areas in which civil society can play a positive role in adaptation to climate change, and concludes that there are five most significant functions that CSOs can perform to promote inclusion of climate change risks in policymaking.

These include augmenting peoples’ access to climate information with CSOs acting as a bridge between research institutions and the people, thus giving voice to the most vulnerable groups. CSOs must also, writes Canales, ensure acknowledgment of the high vulnerability of these groups in public policy through advocacy processes, promote accountability through example as a strategy to ensure quality and transparency for diverse actors’ participation, and promote active participation in inter-institutional coordination at local and national levels.

While most countries rely on State-driven and top-down measures to address climate change, experts opine that local environmental problems are best addressed by engaging local groups and institutions.

Ranjana Kumari, Director, Centre for Social Research, a New Delhi-based advocacy group, says, “Civil society organisations, being closest to local problems, are best suited to creating adaptive capacities within communities while enabling resources to be channelled directly to deserving beneficiaries. They also ensure that the concerns and preferences of those impacted are properly articulated and heard by the authorities and donors.”

The Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR), a Pune-based CSO which works in synergy with state governments, local governance bodies and 28 village communities in drought-prone regions of southern Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, has developed effective rural-based climate adaptive strategies and processes to help local communities.

In rural Andhra Pradesh, for instance, WOTR has taught farmers to monitor rain and groundwater as well as innovative farming and irrigation techniques. This has empowered over a million farmers to proactively whittle down groundwater consumption to sustainable levels.

“We’re also developing application-oriented technologies to provide meteorology-based crop advisories for irrigation, pest, disease, land and nutrient management that optimise land and water productivity,” says Shanti Prakash, a volunteer with WOTR.

National Resources Development Council’s India Initiative on Climate Change and Clean Energy (CCCE), launched in 2009, is working with environmental groups and government officials to help build a low-carbon and sustainable economy.

“We’re engaging with civil society groups and community organizations to better understand the effects of India’s rapid development on the environment and share comparative strategies for reducing air and water pollution and protecting public health,’ explains counsellor Sreedhar Prakash.

In Hyderabad, CCCE is working with technical experts, real estate groups, universities and banks to “increase building efficiency by implementing India’s Energy Conservation Building Code“. The code is aimed at augmenting efficiency in the country’s realty market by improving standards, testing, and harmonization.

Similarly, the Fair Climate Network, a consortium of 24 grassroots CSOs and 24 support organizations launched this year, is facilitating rural communities to develop projects which leverage carbon financing for the sustainable development of some India’s poorest sections.

Indian Youth Climate Network (IYCN) has been using advocacy, campaigning and activism to share inputs on climate change with the youth, one of the groups most vulnerable to climate change. “A more informed audience and a capable workforce can trigger positive change in the environs around them,” explains IYCN co-founder Kartikeya Singh.

While such activity to tackle the ramifications of climate change augurs well for the future, according to Arunabha Ghosh, Chief Executive Officer, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), more work is needed to involve the citizenry in the process as most policies and programmes are based on untested assumptions.

To address this issue, CEEW is conducting surveys in 714 villages across six Indian states to understand the nuances of energy poverty, explains Ghosh. “It’ll be one of the largest such exercises held to date. Hopefully, with such refined results we’ll be able to determine household choices in terms of responses to the energy, water and climate crises.”

Ghosh feels that a big change in India is that environmental issues are no longer fringe concerns for policy wonks or environmentalists. “They’re being recognized as integral to improving the quality of life of communities. But we need to try to find a strategic pathway that combines growth with sustainability. This major shift has still not occurred.”

According to Kartikeya Singh, sensitization efforts need to be stepped up across the country to see a more tangible change and a higher public engagement in climate change issues. “Perceptions need to be broadened to enhance the common man’s understanding of climate change issues to make change all-pervasive and sustainable,” he sums up.