China’s involvement in coal power projects abroad in countries such as India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Vietnam and Turkey casts a shadow over its first Belt and Road Forum

A coal-fired electric power plant in Mongolia. (Photo by Enkhbayar Batmunkh)

Officials and leaders from over 110 countries gathered in Beijing on May 14-15 for the first ever Belt and Road Forum. China’s ambitious attempt to boost economic growth across a vast area stretching from its southeast coast all the way to Africa is known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Its two parts – a Silk Road Economic Belt and a Maritime Silk Road – are focused on channelling enormous investment in infrastructure to connect the region and to open new markets for Chinese products, services and capital.

But the BRI is also causing concern within China and internationally because Chinese companies are investing heavily in coal power in BRI countries. The fear is that China will help lock developing countries into coal-power assets that will last decades, damage people’s health, and contribute to climate change.

See also – Explainer: Will China’s new silk road be green?

Investments on the up

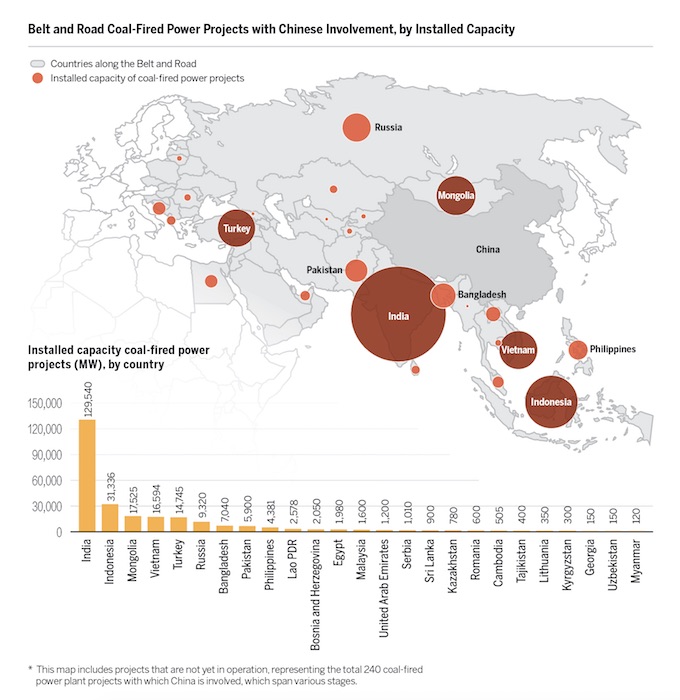

The Global Environment Institute (GEI) has recently carried out a long term review of China’s involvement in coal power projects in 65 countries that are now participating in the Belt and Road Initiative.

GEI’s figures show that between 2001 and 2016 China was involved in 240 coal power projects in BRI countries, with a total generating capacity of 251 gigawatts. The top five countries for Chinese involvement were India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Vietnam and Turkey.

The GEI research also found that China’s involvement in coal power projects in BRI countries, which often takes the form of contracting and equipment supply, has been increasing overall, despite large year-to-year fluctuations.

In the early 2000s Chinese enterprises were encouraged to acquire assets and expand business overseas as part of the government’s Going Out Strategy, leading to an increase in overseas coal projects.

However, there was a steep decline in such projects in 2010 because of policy changes in countries receiving investment, particularly India, which adopted protectionist policies barring foreign participation in domestic coal power projects. Investment in overseas coal projects picked up in 2013 though with the launch of the BRI in 2013, and then slowed following the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2016.

Higher risk expectations

More than 40% of the projects China is involved in are currently in the preparation phase; with 7% still in planning, 15% with contracts signed, and 23% under construction. A further 48% are already in operation, with the rest either cancelled, suspended, or having unclear status based on publicly available information.

The research found international concern around the risks associated with coal projects, interregional laws, diplomacy and national policy all have a bearing on the projected risk of investments.

For example, India, Indonesia and Mongolia have all adopted policies to increase the proportion of renewables in their energy mixes. Meanwhile India, previously the top destination of Chinese coal-power investment along the Belt and Road, has seen relatively little Chinese involvement since a ban on foreign participation in major thermal power projects in 2009.

Limited opportunities at home

China’s effort to reduce coal consumption has put a brake on growth in the sector domestically. In addition, slower economic growth in China has resulted in a decrease in power investments, leading to idle construction and manufacturing capacity, according to Wu Tianrong, director of the International Cooperation Department at the China Electricity Council.

This has fuelled concern that limited opportunities for domestic growth could lead China’s coal power firms to look abroad for new opportunities. The BRI has created the conditions needed for Chinese power firms to work overseas, and there is also strong demand for new generating capacity among BRI countries.

Controversy over coal

However, China’s involvement in overseas coal projects is widely seen as contradicting the country’s promotion of a green energy transition at home, and potentially undermining global action on climate change.

With climate change becoming ever more pressing, the World Bank and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, including Japan and South Korea, have started to restrict financial support for coal power projects, instead encouraging green and low-carbon forms of energy. China’s overseas coal power investments are regarded as possibly “exporting carbon emissions.”

Opinions differ though on the actual size of the environmental and carbon footprints of exported coal-power technology.

Hu Zhaoguang, chief electricity market specialist at the China Electricity Council and former deputy head of the State Grid Energy Research Institute, argues that China is exporting mostly advanced generation technology, with most types of emissions approaching natural gas powered equivalents.

Liu Qiang, head of the energy research office at the Chinese Academy of Science’s Institute of Technical and Quantitative Economics, says that “there’s no reason to criticise China if a project meets local environmental standards.”

But laws and environmental standards in BRI countries receiving Chinese energy investments are often lax, meaning power plants are less likely to keep tight control on emissions.

Development justice

For some BRI countries, coal power remains attractive as a cost efficient means of widening energy accessibility. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) estimates that 460 million people in Asia still lack access to electricity, creating an urgent need to meet local energy needs that often trumps concerns about climate change and local air pollution.

Hu Zhaoguang told chinadialogue that China’s involvement in overseas coal projects is determined by the investment opportunities present in the host countries. For many poorer BRI countries, coal is simply the cheapest available source of power, and that is why it’s chosen.

Zhang Liutong, a senior manager at the Lantau Group, an Asia Pacific energy and economics consultancy, argues that in less developed regions, the cost advantages of Chinese-built projects are key.

In terms of development justice, Liu Qiang says that the poverty relief benefits associated with improving energy access through cheap coal power projects should also be considered when evaluating overseas coal projects.

The lack of energy access has severe impacts on lives and work. In Pakistan, where China is involved in 5.9 gigawatts of coal projects, economic growth has led to rapidly increasing demand for power but generation has long lagged. Over the past five years the country’s energy gap has widened, with supply meeting only two thirds of demand by 2013.

The port city Karachi has recently seen widespread and lengthy power cuts, with local people taking to the streets to protest, leading to outbreaks of violence.

The Port Qasim Power Project, China’s largest overseas coal power investment and the first energy project to be built on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, will supply 1,320 megawatts of power, meeting the needs of four million households.

Dr Keyu Jin of the London School of Economics has written that the key issue with the BRI initiative is “whether there is a clear economic case to be made. Is there a significant benefit, and will that benefit be shared among many?”

Local voices

In other countries, such as the Philippines, there has been widespread opposition to Chinese coal power investments, explains Zhang Liutong, with locals asking if Chinese equipment is reliable and clean enough.

Others are calling on China to shift its focus away from coal projects in Belt and Road countries altogether towards low carbon alternatives.

“Given that India has an ambitious renewable energy target and China being the largest exporter of renewable energy equipment in the world, there would be an opportunity for China to play a much more positive role,” says Nandikesh Shivalingam, a senior campaigner with Greenpeace India.

India has recently published a draft National Electricity Plan that aims to rapidly increase the share of renewables in the country’s electricity mix by 2027, presenting a major opportunity for Chinese companies.

“Chinese investments in Indian coal projects have been declining. At the same time, Chinese investments in India on solar projects are slowly increasing. In 2015, two major investments were announced by Sany Group and Chint group amounting to about USD 5 billion of investment in Indian solar projects,” says Jai Sharda, a founding partner at Equitorials, an equity research firm in India.

Hard questions

Although renewables such as wind and solar are rapidly falling in price, it remains to be seen whether energy investments forming part of China’s BRI will succeed in leapfrogging cheap coal investment in favour of green energy. In the short term at least, a great deal will depend on examining the environmental and social costs of hydro, wind and solar projects on a project-by-project basis.

It will also be up to China, BRI countries and local communities where energy projects are proposed to work together to determine the balance between meeting urgent energy access needs with cheap coal and the broader concern of minimising local air pollution and carbon emissions.

Click here to see the chinadialogue and Bank Watch map of China’s overseas coal investments since 2015. This article was first published on chinadialogue.