The first assessment of IUCN World Heritage sites since 2014 shows a number of surprising trends, including every Asian site having either improved, or been stable

![A rhino stranded by flooding in the Kaziranga National Park [image by: Biju Boro]](https://indiaclimatedialogue.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Kz-Flood1.jpg)

A rhino stranded by flooding in the Kaziranga National Park [image by: Biju Boro]

There is so much bad news for environmental issues at global events that a report that things are improving, or at least not deteriorating, is a welcome relief. For the Conference of Parties (COP23) currently underway in Bonn, Germany, the IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2 report may be that little bit of hope.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), advises the UNESCO World Heritage Committee on issues to deal with nature. There are 206 natural and 35 mixed (with some built up structures) in 107 countries in the list. Their total area is 293,620,965 hectares, or 2.93 million square kilometres. This is equivalent to almost two-thirds the land area of India. These include both terrestrial and coastal areas, as well as a few transnational areas. Since 2015, 13 new sites have been added to the list – from South Asia, the Khangchendzonga National Park in India, was the only one added.

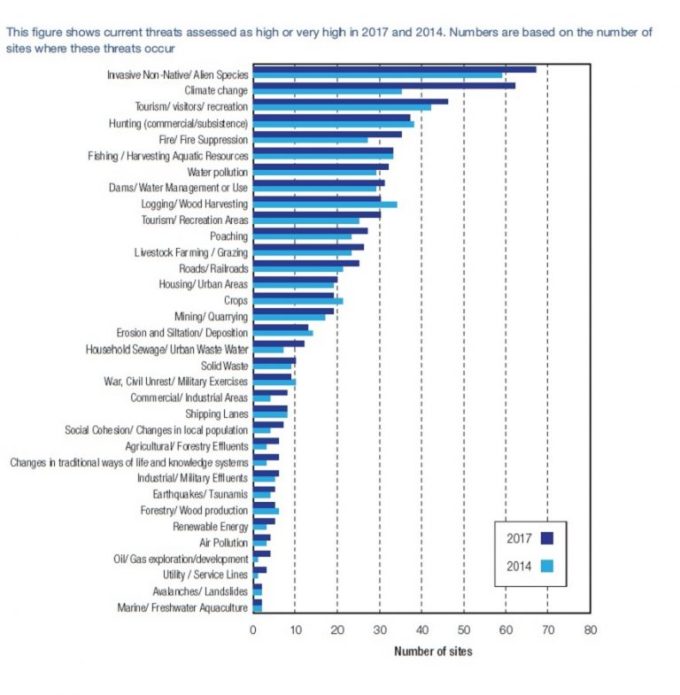

In the World Heritage Outlook, which first came out in 2014, these sites were listed in four categories: good, good with some concerns, significant concerns, and critical. There has been very little significant change in overall numbers. Looking at the high end, in 2017 only 43 sites were assessed as good compared to 47 in 2014, despite new sites being added. But, on the other hand, only 17 were classified as critical compared to 19 in 2014. While overall this leaves us pretty much where we were three years ago, it is in the details that more intriguing data emerges.

Of the 241 sites, 26 changed status in three years, with 14 improving and 12 declining. IUCN assesses the status using three measures: values, threats, and protection and management capabilities. While the last two are self-explanatory, value here refers to the outstanding nature of the site – its beauty and uniqueness, which can be degraded by natural or human actions.

Oddly enough the largest decline in status seems to have happened in Europe, with seven sites showing a decline. In Asia no site showed a decline, and for India there was a special bonus as both the Kaziranga National Park and the Sundarbans National Park were upgraded from the “significant concern” category to the “good with some concerns” group (It is worth noting that the Bangladeshi part of the Sundarbans remains in the “significant concern” category). Africa, too, saw a general uptick in the overall situation of its sites. It is striking that it is not the richest areas that have improved their ranking, although North America remains the region with the highest number of sites (90%) in the good or good with some concerns category.

But while the good news is there, a significant issue is the rise of the impact of climate change. The number of sites affected, or threatened, by climate change impacts has almost doubled, going from 35 sites in 2014, to 62 sites now. In 2014 this was considered the most significant potential threat, and that fear has come true. No other issue, neither invasive species or the impact of tourism, both of which rank in the top three global threats to World Heritage sites, has increased anywhere near as much.

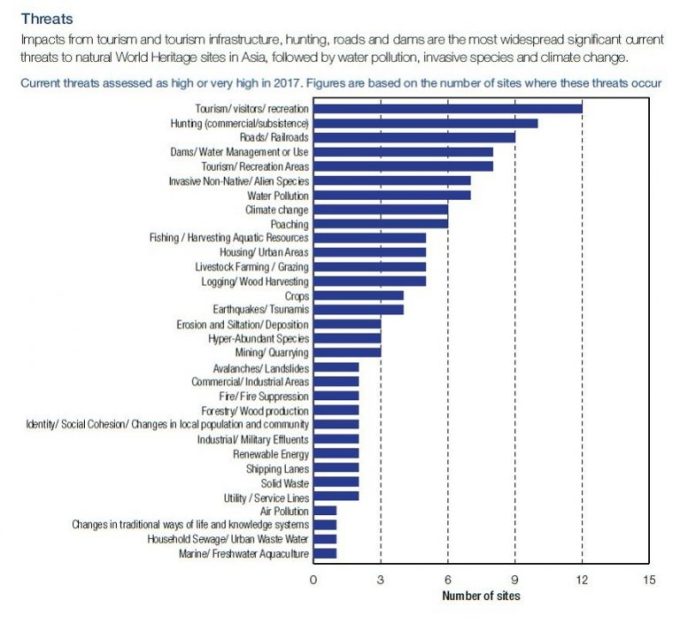

Again it is at the regional level where the more granular data shows up, that trends become more apparent. Climate change impacts, for now, are affecting sites in the regions of South America, and Mesoamerica and the Caribbean the most. For Asia (somewhat like Europe) the most important concern is the impact of human interventions. In fact, the most important threats are tourism, hunting, roads and railway construction and dams. Climate change comes after this, on par with water pollution.

Although climate change impacts are still a significant threat, IUCN seems to assess that direct human intervention is likely to do greater harm than indirect (through human caused climate change impacts). In the context of developing countries that find that weakening environmental controls to make some profit either for tourism, or build development projects through wildlife or other protected areas, this is an important issue to watch out for. Meanwhile, Asia has a small something to cheer about, and India especially.