Between wasteful flood irrigation, free electricity to farmers, and lack of remunerative pricing, Indian agriculture is in a mess, while lack of accountability creates urban water problems

The unrestrained use of pumps for flood irrigation without having to pay for electricity is driving India’s water crisis

The 2019 South Asian summer monsoon is late, slow and inadequate so far. If it makes up somewhat for lost time, those 55% of Indian farmers who do not get irrigation water will still suffer, but there is a chance that reservoirs may fill to the point where people can draw water until January or even February next year.

And then what will people do till next June? For 12 years out of the last 19, water scarcity has been a crisis so common in South Asia before the monsoon arrives, that it is becoming the new normal. The pictures of people again queueing for hours at the few taps in urban slums, or farmers again placing their water jars on bullock carts or tractor trailers and spending a quarter of the day in search of just drinking and cooking water are no longer new. Nor is it shocking any longer that the upwardly mobile in the Indian cities of Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Pune, Gurgaon, and Delhi spend INR 20,000 (USD 290) a month to buy water from private tankers, with the tanker operators drawing more and more water from ever-falling aquifers further and further from the cities.

Are the politicians responding?

The main development promise made by the winning Bharatiya Janata Party in this summer’s election to Parliament has been to provide piped water to every Indian household by 2024. It cannot keep this promise unless it confronts the elephants in the room.

See: Policy continuity and concerns in Indian elections

The biggest elephant is free electricity to farmers. This leads farmers to draw as much water from wherever they can – mainly underground – and use it for terribly inefficient flood irrigation. In a densely populated region where around 80% of water is used for irrigation, which accounts for the largest number of water pumps in the world, and there is no law to regulate groundwater extraction, the result is there for all to see. On top of water scarcity, we have over 60% of India’s population engaged in agriculture that produces around 11% of the country’s GDP. And we have near-bankrupt electricity distribution companies in almost every state.

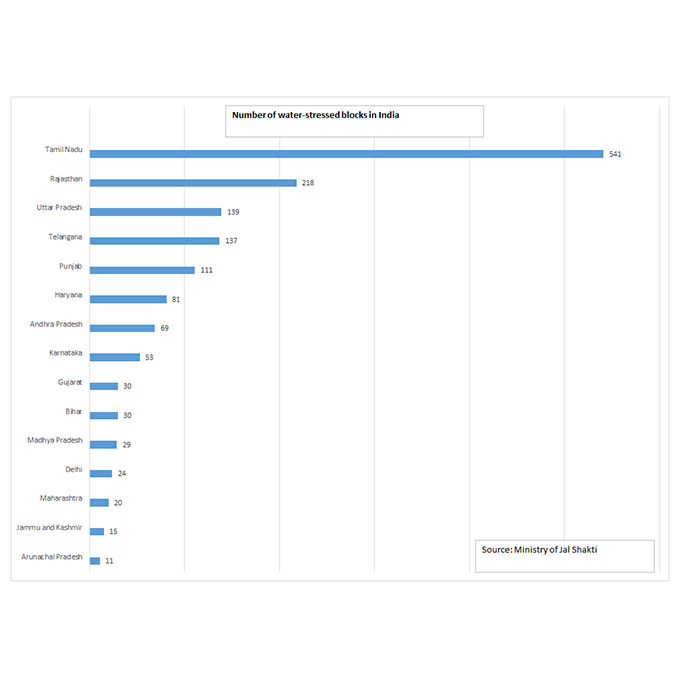

This cannot be solved unless policymakers use a unified lens to look at the water-energy-food nexus, and make the transition from flood to drip irrigation a national priority. India has plenty of schemes to do so, but they have not been prioritised nearly as much as they need to be. The newly unified, strengthened and renamed Ministry of Jal Shakti (Water Power) has made a good start – of the 725 districts in India, 255 are officially identified as ‘water-stressed’, and the ministry has now placed a senior bureaucrat in each district in charge of rainwater harvesting from July to December this year. In all, these districts have 1,593 blocks, and there will be a bureaucrat in charge of each block as well.

That is an important policy change from decades of neglect of traditional rainwater harvesting in India, and it can play a major role in augmenting supply in the lean months. But increasing supply is not going to be enough unless the demand for irrigation water is rationalised. Much of this is tied to the products that the government buys – thus creating a reliable market for farmers. The problem is that these subsidies are, just by the scale of India, broad brush, skewing agricultural production away from local varieties, and undercutting the profitability of local markets.

That is an important policy change from decades of neglect of traditional rainwater harvesting in India, and it can play a major role in augmenting supply in the lean months. But increasing supply is not going to be enough unless the demand for irrigation water is rationalised. Much of this is tied to the products that the government buys – thus creating a reliable market for farmers. The problem is that these subsidies are, just by the scale of India, broad brush, skewing agricultural production away from local varieties, and undercutting the profitability of local markets.

The broken urban water supply chain

Demand rationalisation for urban water is the second elephant in the room. The water crisis in Chennai has hit global headlines this summer, and with good reason, but it is by no means the only Indian city unable to supply water to 30% or more of its residents. There are two reasons. First, water holding structures in the city have been encroached upon by just about everyone including the government – building Chennai airport on top of one of the city’s rivers is a case in point.

See: Mismanaged urbanisation and the destruction of Indian wetlands

Second, building and factory plans are passed by municipal authorities with no concern about where the water for the building or the factory will come from. The question is simply not considered. It has led to Delhi Development Authority – a government body – building hundreds of flats and then being unable to sell any for years because it could not supply water to prospective buyers. And nobody is ever taken to task for this mess.

Instead, the solution found by city fathers all over India is to get water piped from further and further, with very little care for what it will do to the people who had been dependent on this water till now. It is a solution that has clearly reached its limits.

The fact that authorities at municipal, state or central levels are loath to share with citizens is that there is no short cut that will solve the water scarcity crisis. Piping every part of the country will not do it – Marathwada in Maharashtra has an enviable piped water grid, but no water in it when the water is most needed. Nor will the ill-conceived plan to interlink rivers – it will play havoc with the natural slope of India’s river basins and will only succeed in worsening water scarcity in the east and north of the country without improving the situation in the south and the west.

See: Indian government should not use water crisis to justify river linking

South Asia is a region that gets around 80% of its annual rainfall during the four months of the summer monsoon, from June to September. For thousands of years, residents of this region have conserved this rainfall carefully in hundreds of ways that are locally appropriate. We have reached our current crisis by neglecting these traditional methods over the last 100 years or so. While engineering and technical solutions that undergirded an agricultural revolution has led to food security, some of its outcomes are now creating both food and water insecurity. The only sustainable solution is to look at the traditional methods and map them with the technology today instead of neglecting one for the other as we have done so far.