Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has cut federal allocations to tackle urban air pollution by half, even as India’s cities remain among the most polluted globally

Children in Indian cities are routinely exposed to hazardous air pollution (Photo by Tim Gainey/Alamy)

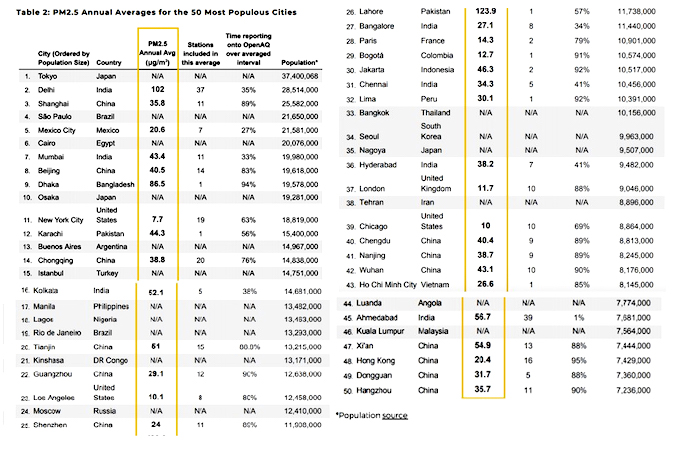

Of the 50 most populous cities in the world, seven are in India. All seven have PM2.5 levels in multiples of what the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends, a study found on the day India’s finance minister cut the central budget for air pollution control despite talking about providing budgetary support to clean dirty air in cities.

Of all the cities, Delhi had the second highest annual average PM2.5 level of 102 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3) in 2019, according to the study conducted by air quality data platform OpenAQ in partnership with the Environmental Defence Fund. Lahore was the worst at 123.9 μg/m3.

PM2.5 is particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less. Essentially, it is fine dust or smoke particles from combustion due to industrial activities – mainly coal-fired power generation – and from vehicle exhausts. These particles get deep into the lungs and the bloodstream and cause respiratory diseases. The WHO recommends a ceiling of 10 μg/m3 in a city.

Instead, in 2019 Delhi had an average level of 102 μg/m3, Ahmedabad had 56.7, Kolkata 52.1, Mumbai 43.4, Hyderabad 38.2, Chennai 34.3 and Bangalore 27.1.

Source: OpenAQ data

While presenting the annual central budget in Parliament on February 1, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman acknowledged the need to “tackle the burgeoning problem of air pollution.” She allocated INR 22.17 billion (USD 304 million) to clean up foul air in 42 cities with over a million population for the financial year starting on April 1.

Slashed by half

However, this was almost half of INR 44 billion (USD 630 million) that was allocated in last year’s budget. Most of that money was not spent, experts said.

“Last year’s funds remained largely unutilised by the urban local bodies,” said Ajay Singh Nagpure, director, air quality at World Resources Institute India, an independent research organisation.

The federal finance ministry had released INR 22 billion as the first instalment in November 2020. “However, as the initial allocation was delayed due to pandemic disruption, it is too early to assess the impact of that funding,” said Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director, research and advocacy at the Centre for Science and Environment, a think tank.

“This year, a concerted effort by the states and cities to develop capacity will help use the allocated funds efficiently and impact on-ground change,” Nagpure hoped.

“While committed funding for clean air action is a positive step, it also raises the expectation of performance-based budgeting to ensure verifiable improvement in air quality,” said Roychowdhury.

Air pollution shortens average life expectancy in India by 5.2 years compared with what it would be if WHO guidelines were met, according to Air Quality Life Index 2020 by the Energy Policy Institute of University of Chicago (EPIC).

In cities like New Delhi, Delhi, life expectancy shrivels by around nine years from breathing filthy air, a situation that can be reversed only through drastic policy changes and action.

See: Air pollution robs over five years of life in South Asia

Poor countries, dirty countries

While the situation in India and China is the worst, OpenAQ found that 33 of the largest cities in the world exceeded the WHO PM2.5 limit by around four times in 2019. The pollution is far more acute in developing country cities than in developed countries.

The worst affected cities were in Asia – Lahore (Pakistan), New Delhi, Dhaka (Bangladesh), Ahmedabad and Xi’an (China), in that order.

Air pollution is a bigger killer than the Covid-19 pandemic and will continue to remain so unless there is strong and sustained policy action to tackle the problem, researchers at EPIC said.

It is a wake-up call for everyone to download air quality sensors on their smartphones or to buy a low-cost sensor, OpenAQ researchers believe.

All the sensors are not equally good, but they provide an indication that helps fill key monitoring gaps and enables cities, governments, researchers and citizens to participate in monitoring air quality and fighting air pollution in their communities.

The researchers point out that 90% of the world suffers harmful pollution levels, yet only half have access to air quality data.

OpenAQ collects its data from a coalition of research scientists, NGOs and individuals. It uses high quality reference grade sensors that cost around USD 10,000, as well as low-cost sensors that cost around USD 100. The platform houses more than three quarter billion data points from over 11,000 stations in 99 countries. It is available to everyone, free of cost.

Many scientists working in government-run laboratories criticise low-cost sensors, but these sensors are improving all the time. Many are mobile. Their use widens the areas that can be monitored in a city quite dramatically.

Information can spark action

Speaking at the release of the study, Jeremy Taub, executive director of OpenAQ, said, “We want to encourage new, affordable solutions to monitor air quality, and bring that data to OpenAQ to increase funding and action for those communities who are most affected by air pollution. It will fill important data gaps allowing communities to develop solutions to air pollution.”

“One of the keys to fighting air pollution inequity is data transparency — ensuring that as wide a range of people as possible have access to as much of it as possible,” said Millie Chu Baird, Associate Vice President at Environmental Defence Fund. “It’s foundational to the ability to take action.”